Jekyll Blog Speed

Reducing the time to meaningful first paint Jekyll blog

Published by Vincent Pickering

on

I decided to set myself a challenge.

Over the past few weeks, I have spent pockets of time reducing the overall page weight as much as I possibly can and decreasing the Time To Meaningful First Paint.

My current score on Google’s Lighthhouse plug-in was 84 out of 100. This wasn’t a bad score, but I knew I could easily get to 100 out 100 by adding a service worker.

I’ve been wanting to implement a Service Worker on my site for some time now.

I spent some time reviewing other people’s work. Service Workers are not a new technology and I knew others would already have solved most of the major problems. Jeremy Keith has a really nice implementation I liked, but it felt a little overkill for what I required. My basic need was to cache a few pages for offline use, and for any other requests to be directed to an offline page.

After further digging I decided to use Harry Roberts implementation and tweak a few things. This made sense as Harry also has a Jekyll blog and his needs are much the same as my own.

After implementing the service worker I achieved the 100 score on the Lighthouse plug-in. But I knew I could go further.

## Simple Jekyll Cache Busting

Firstly I wanted to ensure that assets got cached if they hadn’t changed and users only downloaded newly updated content.

There is a really simple way to do this using Jekyll global variables. Open up your _config.yml file and add the following line:

~~

version : 100

</~~

Next any asset you want cached add a question mark followed by an equals sign then call the Jekyll site variable like so

In essence (this is telling the browser that by using the query parameter in the URL) if URL has changed the content has changed so fetch it again.

Now every time you update any of your assets, remember to update this variable in the config file and when the site is republished the browser will know to fetch the latest assets.

I have replaced this with a much simpler method to output the current date/time as a parameter.

<link rel="stylesheet" href="/css/application.min.css?v={{ "now" | date: "%Y-%m-%d-%H-%M" }}">Adding Cache Control on Netlify

If you wanted to control your cache headers you would usually need to include a .htaccess file. My blog is hosted by Netlify who use a slightly adapted interpretation of this. Instead of creating the .htaccess file, create a _headers file.

While we are creating the file. Don’t forget to modify your Jekyll _config.yml file to include a file with an underscore, or it won’t be built correctly on the Netlify servers. We can do this simply like so:

include:

- "_headers"So my _config.yml file in complete looks like this:

# Markdown

markdown : kramdown

#Syntax Highlighting

kramdown :

hard_wrap : false

# syntax_highlighter : rouge

# Outputting

permalink : /blog/:title

timezone: Europe/London

# paginate: 20

# Site Variables

title : Thoughts on frontend development

description : Web design including UI, UX, HTML, CSS, JavaScript and Node

url : https://vincentp.me

version : 800

available: true

# Exclude Files

exclude:

- "postcss.config.js"

- "Gemfile"

- "Gemfile.lock"

- "package.json"

- "node_modules"

- "LICENSE"

include:

- "_headers"Now we have the blank _headers file added and building correctly lets add some cache control and basic header protection:

/*

X-Frame-Options: DENY

X-Content-Type-Options: nosniff

X-XSS-Protection: 1; mode=block

Cache-Control: public, max-age=31536000

{% endraw %}This does the following:

- Line 1 prevents other people loading our site inside their content. This protects against malicious actions.

- Line 2 prevents a browser from changing the content from text/html as it is declared.

- Line 3 prevents cross site scripting attacks.

- Line 4 is the length of time we should cache any assets the browser downloads from our site.

Line 4 is all you need for the caching performance, but as a general rule the first three lines of code are a sensible precaution to include on any site.

So far so good. I’ve managed to bring repeat render time trips down considerably by caching the content using a Service Worker and implementing a caching strategy for assets.

CSS

A key concern in ‘Time To Meaningful First Paint’ is the CSS.

I’ve done a large amount of work optimising my CSS and so far gotten it to 5kb in size. Linking from a CSS file will mean 1 additional round trip for the browser. It would need to fetch the HTML page and then go and request the CSS file and finally it would be delivered. The round trip costs time, the time to then read the code and render it out also takes time.

My current implementation was to inline all the CSS, this is quite a simple thing to do in Jekyll. Instead of exporting your compiled CSS/Sass/Less in to a css folder export the file in to the _includes folder.

Then to include the CSS inline do this in your HTML file, the same as your would include any other file in the _includes directory:

<style>{% include filename.css %}</style>The file size is small so I assumed this would be the fastest way to deliver the content. But I wanted to explore another method I had used before on a large scale site and see if this could speed things up further.

HTTP2 Server Push

Server Push is a relatively new technology. It allows us to declare when a browser requests a HTML file that you will need the following other assets so I’m sending them now along with the HTML file.

Traditionally what happens is that the HTML file is requested then parsed. Once it’s parsed the browser identifies external asset links and requests those files be sent. This can amount to alot of “chatty” requests on the network even for a simple webpage.

If you use:

<script src="someURL.js"></script>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="someCSS.css">

<img src="image.jpg">or anything else that requests a separate resource, this requires the browser to request the asset(s), the server to respond and deliver the assets. Finally the browser has to render the page.

Certain assets such as JavaScript can block the rending of the page. If they are requested the browser will not render the page until the assets has been retrieved. This is because JavaScript can modify the DOM so the browser waits to retrieve the file before it tries to render the page.

By using Server Push, we can tell the browser. Your definitely going to need this file so I’m sending it to you now. The files are sent in parallel to avoid slowing down the page load and it eliminates the additional round trips a browser will need to render the page.

Implementing Server Push on Netlify is pretty easy. The following code is from KeksiLabs.

/

Link: </style.css>; rel=preload; as=stylesheet

Link: </main.js>; rel=preload; as=script

Link: </image.jpg>; rel=preload; as=image

Cache-Control: private,max-age=0

/subpage/

Link: </style.css>; rel=preload; as=stylesheet

Link: </main.js>; rel=preload; as=script

Link: </image.jpg>; rel=preload; as=image

Cache-Control: private,max-age=0

...Stepping through this line by line.

- The slash, says all top level pages requested should to the following.

- The next three lines show how to PUSH a CSS, JS or image file.

- The 4th line dictates the caching rules to follow.

- The subpage line shows how we can override the above rules for pages that are an exception.

It is important that we only send the absolute vital content this way. The aim is to render the page above the fold as quick as possible. Don’t flood this file with anything that isn’t absolutely vital. Keep the requests few and the files as small as possible.

A good technique to increase rendering speed is to move only the essential CSS content needed above the fold to an inline file. The rest of the CSS content is put in an external file. You then use Server Push to send the external file at the point the page is requested. Critical styles inline mean the page is rendered almost instantly and anything out of the viewport is rendered quickly without the round trip delay.

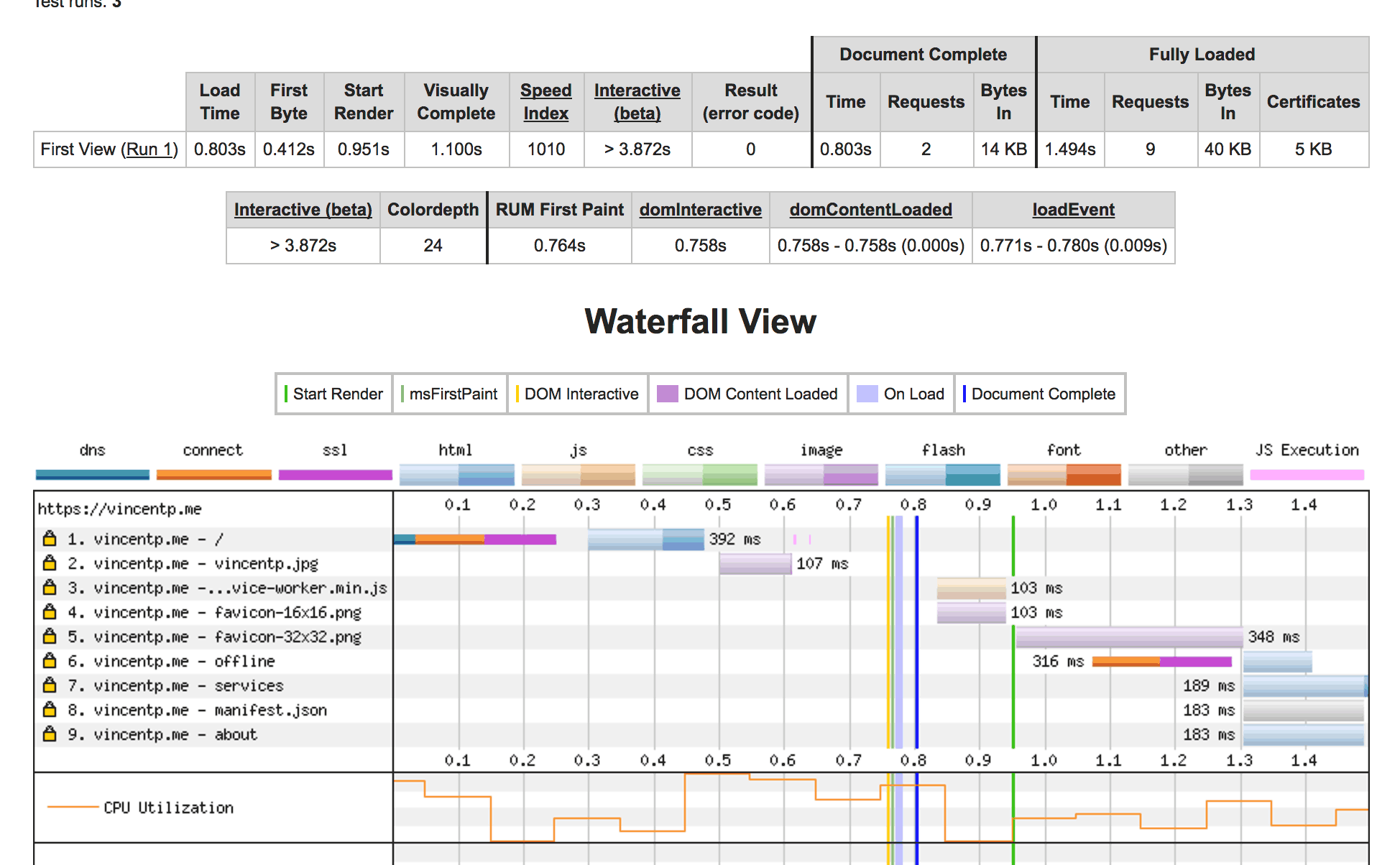

I implemented Server Push, inline only my critical resources and tested my site using Webpagetest.org.

To my surprise I found that I had actually increased my Time To First Paint by 300ms!!

I’ve concluded that this is down to my total payload of the HTML + all my CSS inline being under 15kb (15kb is the maximum that can be sent back in the initial request).

I am deferring my service worker until after the page is loaded. Any request for a resource happens, after the initial 15kb is received and processed, but before the server has finished sending any additional assets. Due to the files being so small I could see in multiple tests on Webpagetest.org that resource were being sent twice. Once from the header and once requested from the page.

I’ve used this technique with larger sites before to great success. So I believe this is definitely down to the overall payload being under 15kb, unless someone can point out a flaw in my logic?

Recap

So to recap what I have done.

- I implemented a service worker.

- I adding caching to my assets by using a query parameter.

- I added cache control to my headers file.

- I inlined all my CSS due to its small file size.

- I tried to use Server Push, but didn’t see any benefit. Again possibly due to my smaller file sizes.

All my code is available on my repository. So feel free to dig through it and ask me any questions.

Here Be Dragons

Given this exercise and my conclusion to inline all my CSS there is now one small, tiny problem. Each page now contains a reasonable chunk of CSS that isn’t required per page.

A future (and potentially mad) exercise is to only import the styles I need in to each template. I’ve been mulling over various implementations with Jekyll for this and potentially ditching PostCSS and moving back to Gulp to facilitate a more complex set-up.

The complexity of implementing different CSS files per template, versus any speed difference noticed by the end user for such small margins could be a rather fun blog post for the future.